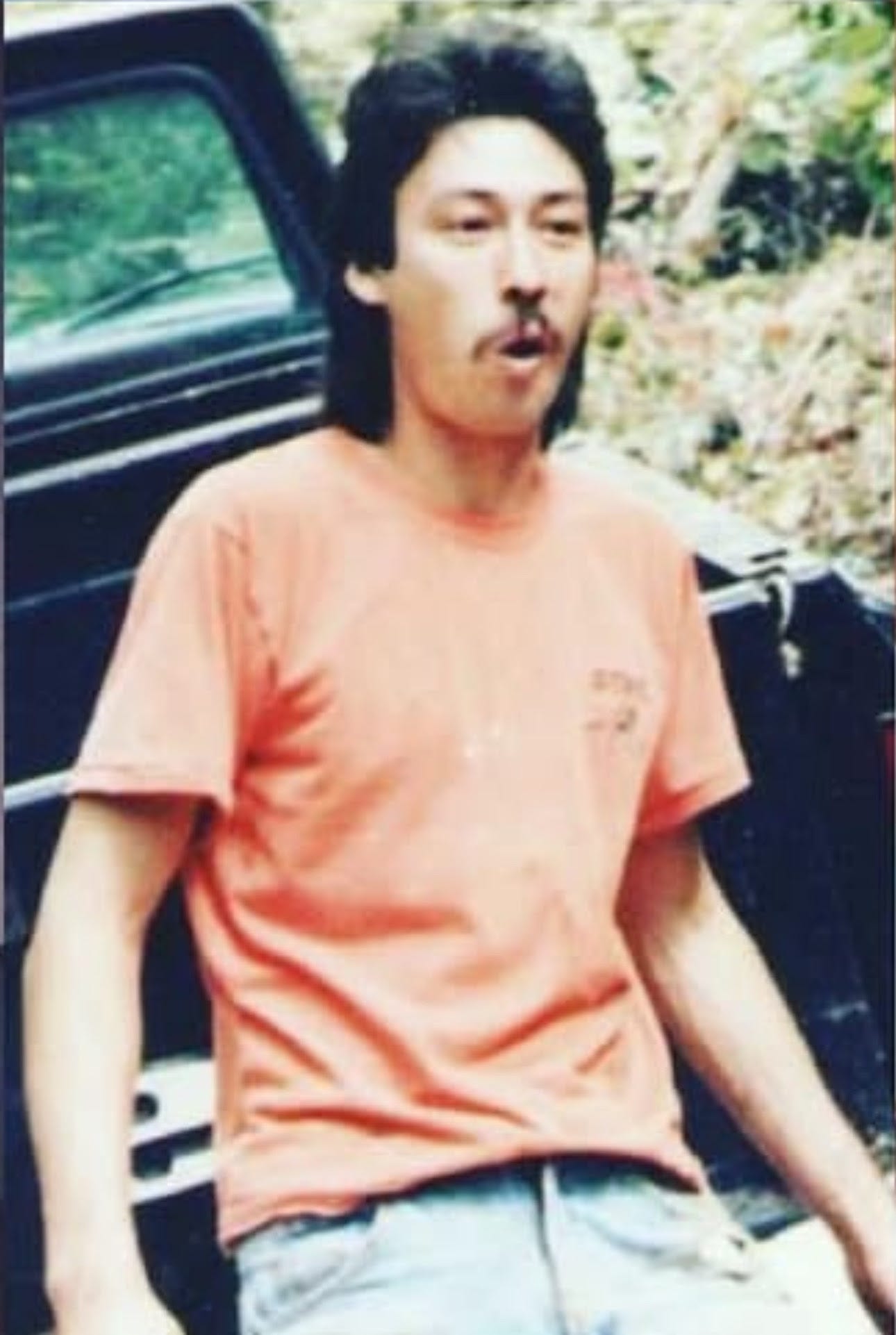

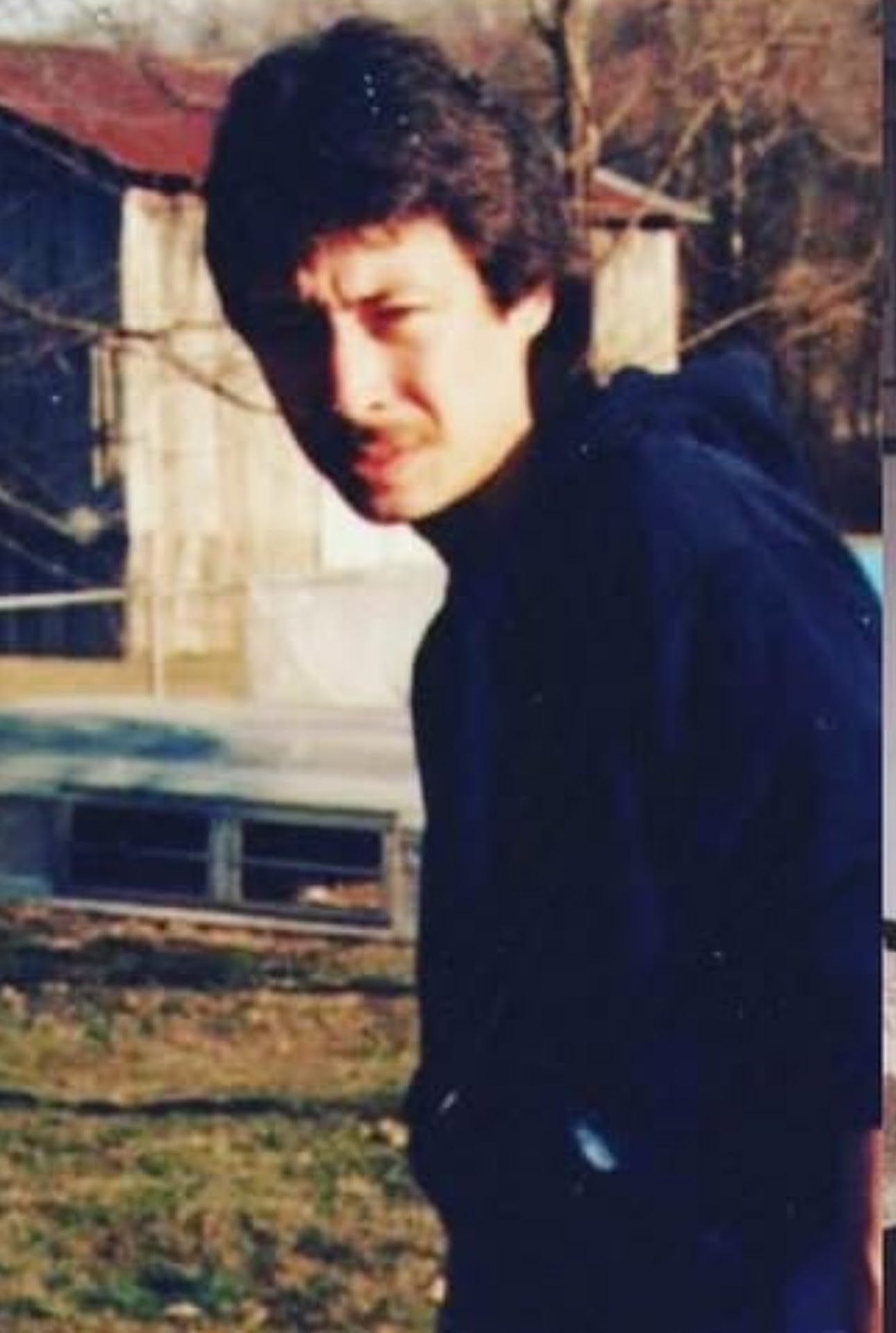

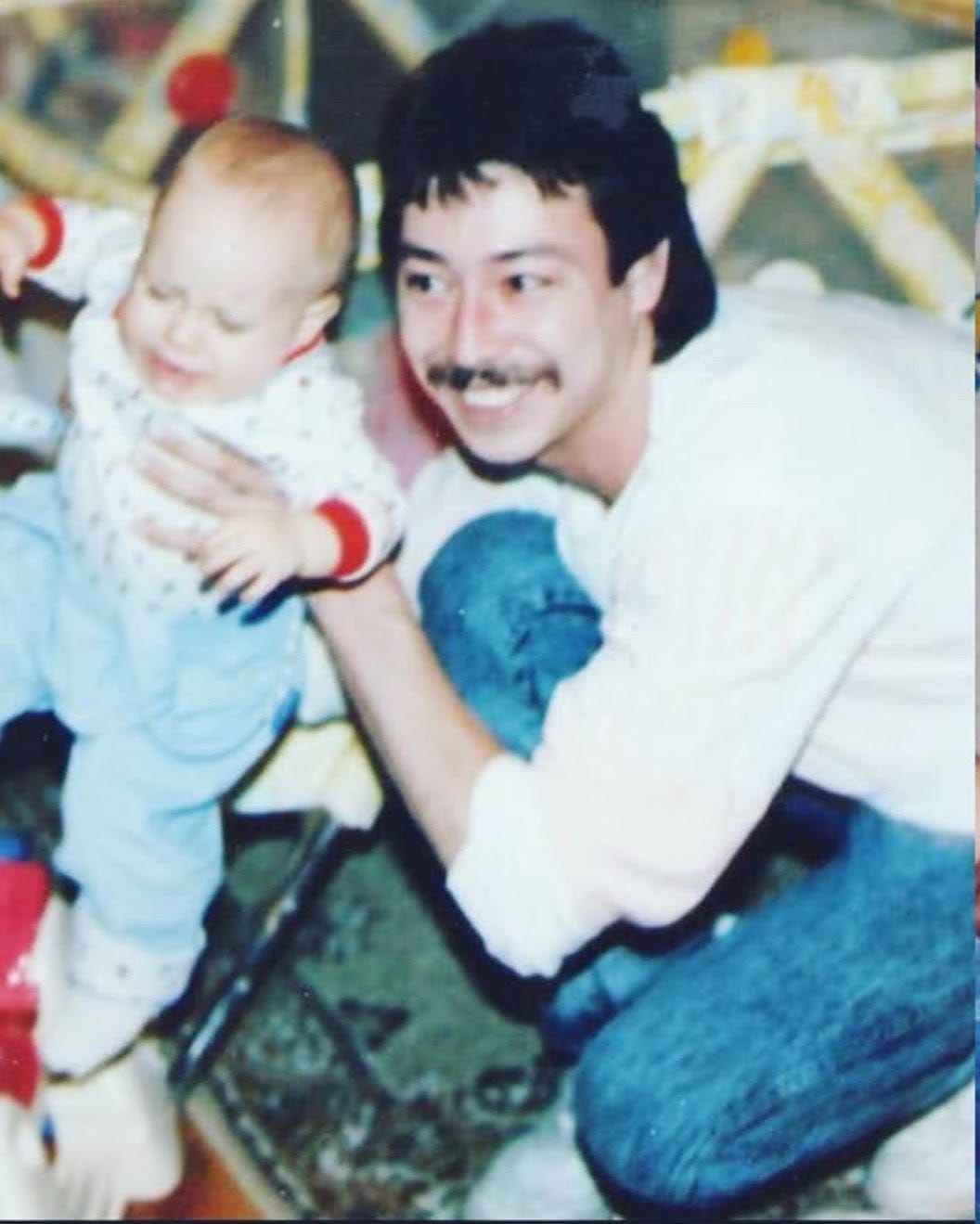

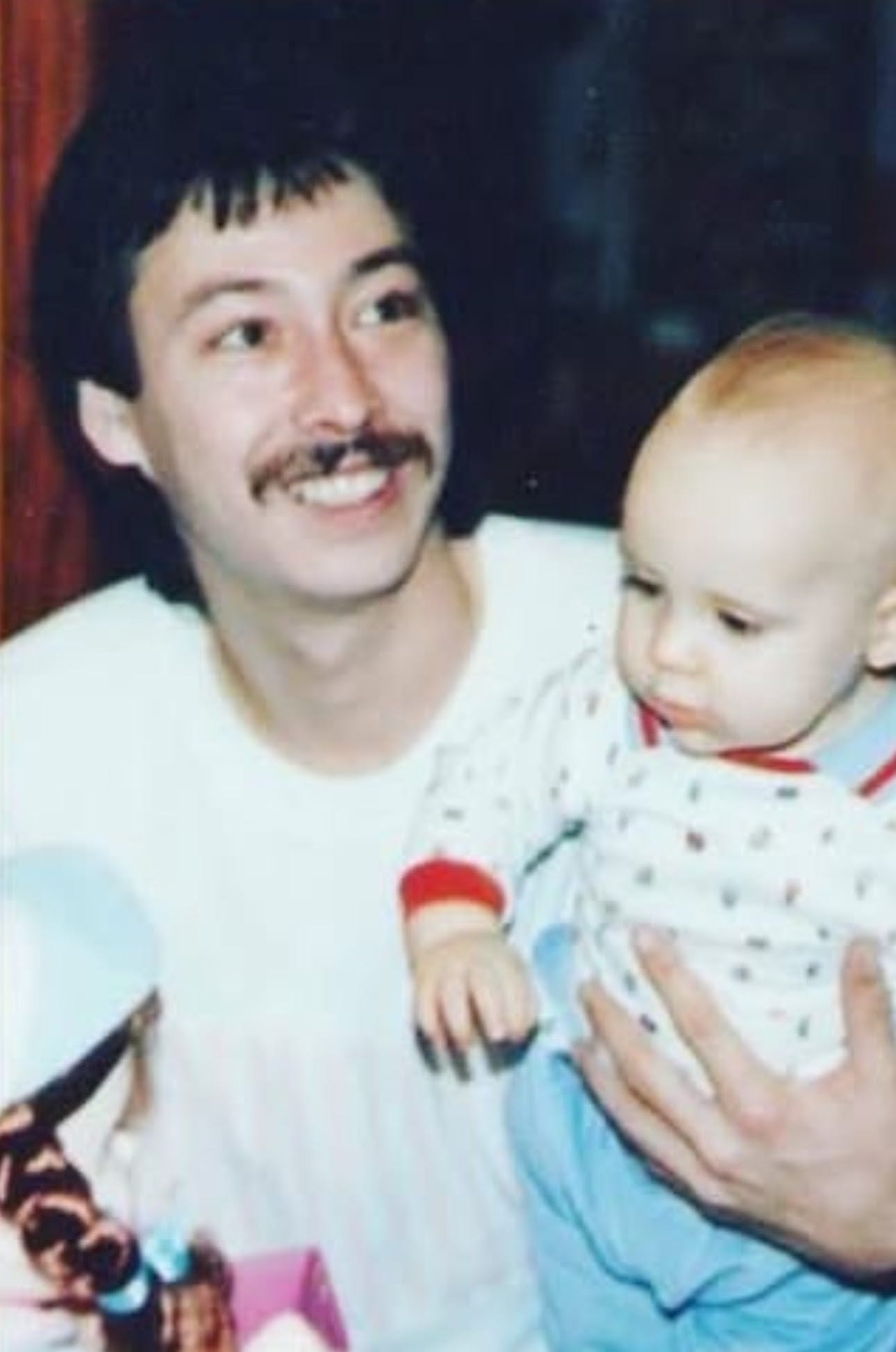

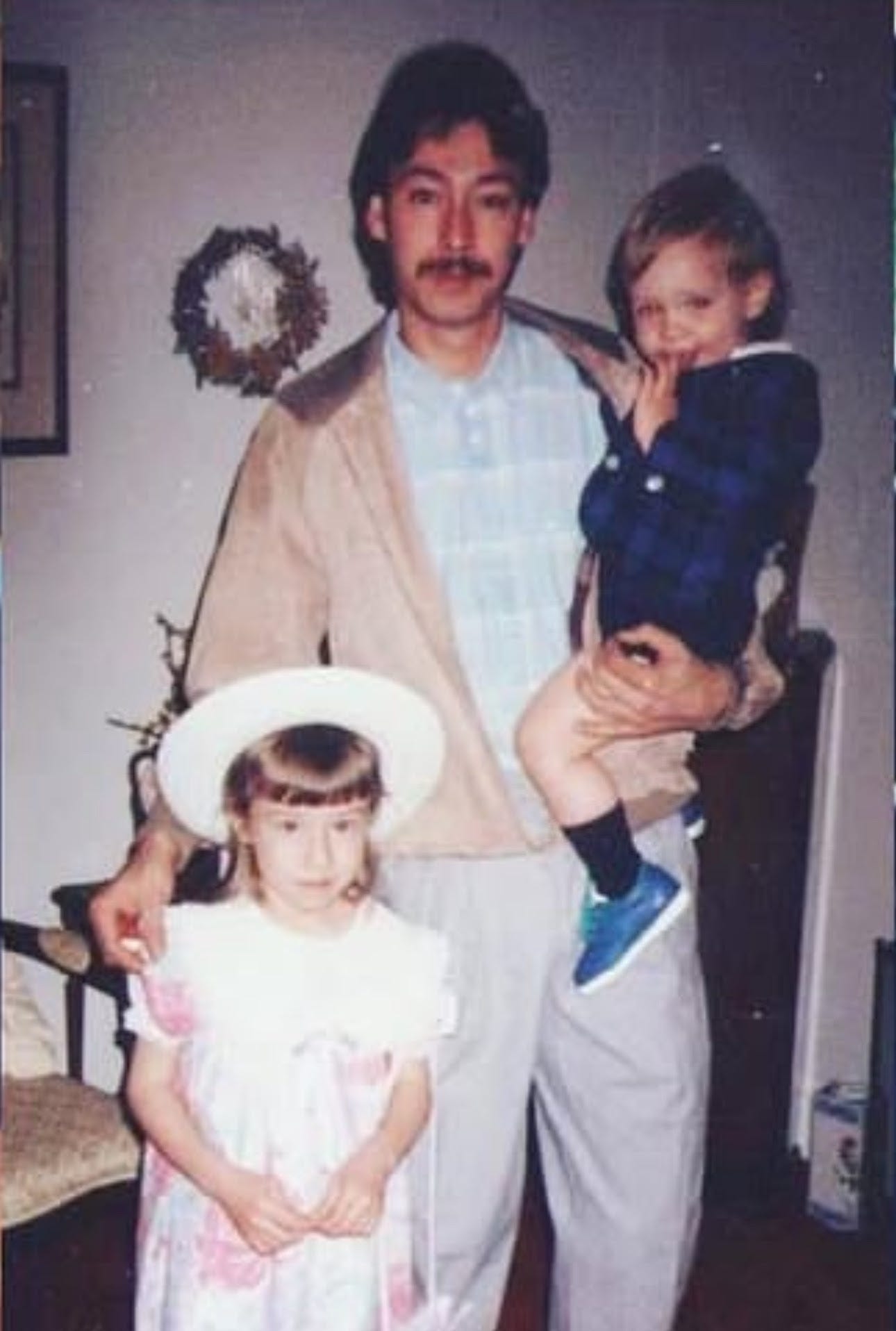

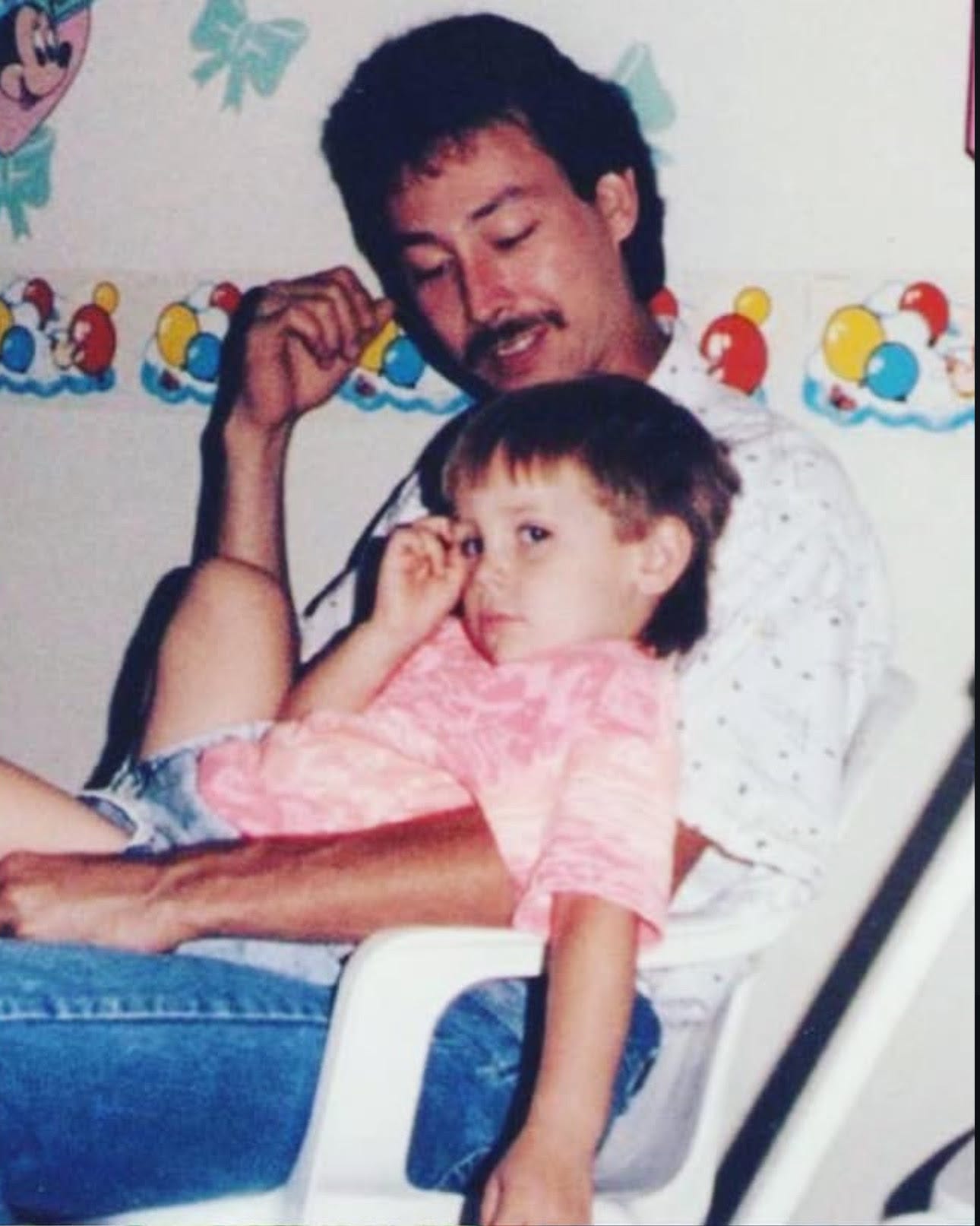

This is a piece about grief, unexamined trauma, and an attempt to kickstart a long overdue healing process — two decades later. It’s also dedicated to the memory of my dad, Jerry Trent Street. I love you, Dad.

The worst Easter

If there’s one thing I’ll never forget, it’s the sound of my mother‘s footsteps as she came upstairs on the morning of Easter Sunday in 2005, exactly 20 years ago today. “I don’t know how to tell you this,” she said as her eyes filled with tears. “There’s been an accident. Your dad passed away.”

That wasn’t the first time I had lost someone, but it was close. Four years prior, in February of 2001, we lost my grandmother on my dad‘s side. I was 12 then, and because my parents divorced a decade earlier, and due to circumstances that were often beyond my control, I didn’t get to spend as much time with my paternal grandparents as I would’ve liked. Losing my Japanese grandmother, Fumiko, was the first time I can remember feeling regret for things I never got to say. Days I never got to spend. Culture I never got to learn.

March 27, 2005 would be the second time I would feel that same regret. But this time, it would be worse. So much worse. Because on the day that my dad passed away in an overnight car accident, I was just over a week away from my 17th birthday. I was nearly finished with my junior year of high school. I was driving now, able to make more of my own decisions about how and where I spent my time. I distinctly remember wanting to make more space in my life to get to know my dad. To understand where he had come from, and to bond with him as an adult and try to make up for lost years.

Family values

It’s not that I never saw my dad growing up. I spent weekends with him, visiting with that side of my family, including my stepmother and half siblings. We spent our days in the pool, playing in the woods, shooting basketball at the goal up the street, climbing trees, getting stuck in mud pits, watching Beavis and Butt-Head and South Park late at night after the grown-ups went to bed, playing video games, hunting arrowheads (a favorite pastime of my dad‘s), and having game nights in the den. Weekends at Dad’s felt pretty normal. Almost like spending the week with him, just compacted a bit. We would go on summer vacations to Myrtle Beach, and Dad would go out of his way to make sure all of us had a great time. It’s hard to remember a time around him when he wasn’t smiling or laughing. He had this infectious laugh that I can still hear clearly, even 20 years later.

There is no question in my mind that my dad loved me. And I loved him. But there were some years during my early adolescence, from about age 12 to age 16, when my weekend visits to see Dad and my other family members started to diminish a bit. I’d skip a weekend here and there, sometimes even two. I started to see less and less of my siblings. I was a member of the high school band and just about every club you could possibly be in. Plus, I started dating, and I became so busy with being a model student, that my priorities shifted a bit. My dad worked out of town a lot, so there were weekends when he would be gone, and also weekends when I would have other plans with my girlfriend and friends. Finding common times for visits became more complicated.

There is no question in my mind that my dad loved me. And I loved him.

But as I got older, I remember thinking about how important it was to maintain good relationships with my family, especially with my parents. Both of my parents loved me and wanted a good life for me, but it was always clear to me why they didn’t work out. They held vastly different views and values and notions about what success looked like in life. Neither of them was wrong, because obviously there’s no one right way to live. But I think my mom was especially predisposed to believe that I needed to keep my head down, my shoulder to the grind, and throw myself into my schoolwork and extracurriculars, no exceptions and no wiggle room. Because I spent the most time with my mom, her mindset became my mindset. I adopted those same values, and I made sure that school was always my first priority. I had perfect attendance all the way through school, and I made straight A’s my entire academic career (except for one borderline B in the third grade, which resulted in my being grounded, and subsequently led me to strive for higher grades for the rest of my time in school).

2,339 out of 2,340 ain’t bad

Before I go any further — because what I just told you is relevant to what comes next — I want to make it perfectly clear that I do not blame my mom for instilling these values in me at an early age. Her insistence on my academic success was rooted in her desire for me to be successful and have a better life than she experienced growing up. I am of the mindset now, and have always been, that my mom raised me the best that she could with the knowledge and resources that she had available to her. She was not always dealt the best hand, and my family rode the highs and lows of life, just like any other family, but there isn’t a doubt in my mind that my mom put all of her energy and love and sacrifices into making sure she raised a good son who would go on to be happy, healthy, and thriving.

With that said, this is the part where I tell you I graduated high school in 2006 having missed one single day of school out of 2,340.

That was the day we buried my dad.

(Mis)remembered?

Memory is such a strange thing. We sometimes think we are so sure that something happened in exactly a certain way, and we commit that event to memory. And whether it actually went down that way or not, that becomes the memory of record that we draw on for the rest of our lives as we tell the stories that shape us. I say that to preface this: On the day before my dad‘s funeral service, I have a memory of relaying to my mom that his graveside service would take place the morning after the funeral, and having her look me in the face and ask me, bluntly: “Are you going?”

Was I going? To my dad‘s burial service? What kind of question was that? That’s my dad. I’m a 17-year-old boy in high school who just lost his dad. Of course I’m going to his burial service.

“Well, that’s a school day,” I remember her saying. “What about your perfect attendance?”

My perfect attendance. Eleven years of it. But guess what? Up until that moment, it had not even crossed my mind. All that had crossed my mind was that my dad had died, his funeral was the next day, and the day after that we would be putting him in the ground forever. Suddenly, and unfairly, I felt a heavy guilt. I would be breaking a pattern of excellence that I had established as a student. A pattern of perfect attendance. And as we’ve already established, that was a value that was instilled in me at a very early age. And here it was being brought up as a reminder. My mom, whether she meant to or not, had transformed an event that was, up to that point in my life, the most traumatic thing I had ever gone through, into a dilemma that really wasn’t a dilemma at all: Do I go to school and maintain my record, or do I go say goodbye to my dad with the rest of my family?

I can confidently say that I don’t think any other kid in my class, or any other kid in school, would have even been presented with such a choice. And even if they had, I definitely don’t think many, if any, would have felt the weight of having to make that decision the way I did in that moment.

I say again that memory is a fickle thing, and I cannot state with certainty that my recollection of that conversation is fully accurate. And I do want to reiterate here that I do not blame my mom for the values she tried to instill in me. I don’t for one minute believe she intentionally spun me into a moral crisis by pitting my duty to attend my own father‘s burial service against my desire for a perfect school record. But that is the reality of what I felt that day.

Was I going? To my dad‘s burial service? What kind of question was that? That’s my dad. I’m a 17-year-old boy in high school who just lost his dad. Of course I’m going to his burial service.

I can tell you, thankfully, that I chose to miss school for the service. I chose to join my siblings, stepmother, family members, and many of my dad‘s friends, as we said goodbye to the man I desperately wanted to get to know more, but never would get the chance to.

I don’t regret it. I have never regretted it. In fact, I think if I had chosen to go to school that day and miss that service, not only would my grieving family members have resented me for that decision, but it would have eaten me alive for the rest of my life. Couple that with the lifetime of missed connection with my dad I was already facing, and I’m not sure I would have survived the emotional and mental strain.

Perfect attendance, imperfect goodbye

And now here we are, 20 years later. Twenty years! That’s a long time. It feels like I should be able to tell you that I have learned a lot about myself in that time. That I have learned more about the man my dad was. That I have stayed connected with that side of my family, and have found ways to honor his memory. That I have visited his grave regularly, paid my respects, and found ways to bond with the memory of my dad, if not the man himself.

But. You knew there would be a but.

This is the hardest part of this entire piece. This is the part where I tell the whole world something that I have kept secret for all the years that have passed since then. I don’t know if it’s something most people would think too hard on for themselves, but when I tell you I have a deep and profound sense of shame for what I am about to say, it is neither hyperbole nor overstatement. Here it is:

I have never – not once in 20 years since the day my father’s casket was lowered into the earth – visited his grave. Not even to say my own individual goodbye to this man I feel robbed of knowing.

I could wax poetic about all the reasons I believe visiting cemeteries seems like an exercise in futility to me. I could go on about the fact that I don’t believe our loved ones are in those graves, so what does it matter if we don’t visit them? I could honestly write an entire essay exploring human burial traditions and the reasons we do the things we do after our loved ones have passed. But that’s not my focus here. The truth is that I haven’t visited that grave because I am afraid of what I might feel if I do. I am afraid that my mind will take me back in time to 20 years ago, when I was presented with an impossible choice. And even though I made the right one, the fact that there was any consideration at all given to the other option still haunts me a bit to this day.

But that’s not all. Like I said, 20 years is a long time. And although I haven’t visited my dad‘s grave in that time, I have learned a lot about myself. I have lived a lot of life in those two decades. I have gone on to college. I have worked a multitude of jobs. I have lived in other cities. I have loved and lost, and loved again. I have opened and run businesses, made art, directed movies, published books, and on and on and on. I have finally told the world that I am a proud, bisexual man, and I publicly and happily announced my love for my partner, John, who is such a rock and supportive presence in my life.

There is no doubt in my mind that my dad would be so happy that I have found success and fulfillment in the arts. Dad was himself a gifted sketch artist. He loved to draw and he was wicked good at it. Just about every weekend, he would have a dozen or so new sketches of birds that he had drawn. He was so meticulous about every line, every shaded area. He would sketch and then color in his drawings, and I always remember telling him, “Dad, you could print and sell these as postcards or something!”

But what about the other parts of me? The bigger parts? What about the things I never got to share with my dad? How would he feel about the fact that I have a boyfriend now? What would he think about the choices I’ve made in life to get where I am? What would an adult relationship with my dad have been like? This is something I have thought about many times over the last decades. I imagine that, if he had lived, and if I had gotten to spend more time with him as I had hoped at 17, before that fateful Easter Sunday morning, we would have had a good relationship. Dad was always easy to talk to as a kid. I never felt judged and he always had this way of hearing you out. He would tell you what he honestly thought, but he would wait and let you get it all out first. There was a patience about him, at least with me. And I like to think, or maybe hope, that my dad would have accepted me exactly as I am, and would have embraced John and treated him like a son.

I have never – not once in 20 years since the day my father’s casket was lowered into the earth – visited his grave.

But I’ll never know that for sure. I’ll never know. And that’s another reason, I think, that it’s so hard for me to visit that grave. Because even though I know my dad isn’t actually there, and even though I’m not especially religious these days, there is a part of me, just this tiny piece, that worries I might actually hear his voice there, and that I might not like what it has to say. What if he’s not proud of me? What if he doesn’t approve of me? What if there was resentment in him at the end? What if part of him feels I didn’t try hard enough to spend more time with him?

What if, what if, what if…

The plan is…there is no plan

So, that’s where things stand now. I don’t write these words to declare to you that I plan to take some kind of action. I haven’t had any sort of epiphany that makes me feel led to actually go and visit my dad‘s grave. I don’t have an impending sense of catharsis that would come from finally doing that. I guess the real reason I wrote this is because it has felt like a weight I have carried for 20 years. Maybe it’s silly. Maybe no one else thinks that’s a very big revelation. Maybe there are others out there who have also never visited the graves of loved ones. I can’t know for sure. What I do know, and what I’m trying to be very honest about here, is that I do feel shame about it. There is a part of me that does, indeed, feel I should rectify two decades of negligence when it comes to visiting.

But there is another part of me that wonders: What will I take away from that experience if I decide to do it? Will I hear my dad‘s voice? It was awfully distinctive, after all. And if I do hear it, what will it have to say?

And, most importantly, will I walk out of that cemetery feeling better or much, much worse?

Love you and this so very much!

Thanks for sharing. ❤️

I lost my mama 11 years ago. I haven’t gone to see her grave since the day she was buried. I’ve been to the same cemetery since (the day we buried my grandpa), but I didn’t go see her grave. I couldn’t tell you exactly why. I think some of it is just the knowledge that she’s not really *there*, and some of it is the constant wondering what she would think of me now. I entirely understand all the feelings involved.